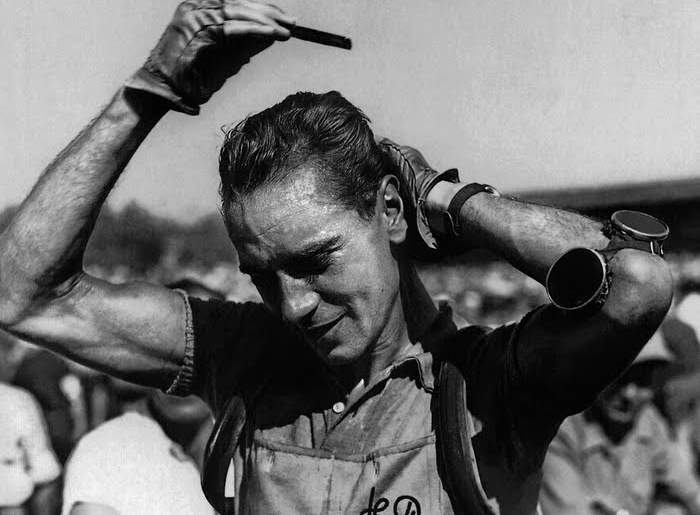

Hugo Koblet, “Pédaleur de charme“, and Fausto Coppi, “Il Campionissimo”, two post-war era giants. They were good friends, until the Giro d’Italia 1953 edition. After that Giro, they would never speak to each other again. But, what happened?

Giro d’Italia 1953

Before the 1953 race, Hugo Koblet was the first and only non-Italian winner of the Giro (he won in 1950). He came to the race in superb form. Coppi, on the other hand, had already won the Italian grand tour four times and was looking for a fifth victory.

To date, another campionissimo (champion of champions), Alfredo Binda was the only five-time winner of the race, and being dubbed as the next Binda, a fifth victory was very important to Coppi.

An important aspect of the 1953 Giro was the first use of Passo dello Stelvio. With an elevation of 2,757 m (9,045 ft) above sea level, it’s the highest mountain pass ever crossed in any grand tour.

It has 48 hairpins, and it was not asphalted back then. Today, it holds an iconic place in the world of cycling (it is the highest and most iconic Cima Coppi today). It is like the Alpe d’Huez of the Tour de France, but much grander, much bigger.

In the fourth stage of the race, a 171 km (106 mi) mountainous course from San Benedetto del Tronto to Roccaraso, one of the unwritten traditions of cycling was born: waiting to the race leader, if s/he crashes or having a mechanical problem.

Koblet crashed into a little girl. She was unharmed but Koblet’s bike was ruined. A few minutes later he got a new bike but it seemed like his hopes of winning the Giro were ruined. But, when the leading riders learned that Koblet was chasing desperately, they stopped racing and waited for him.

Koblet won stage 8, a 48 km (30 mi) time-trial from Grosseto to Follonica, and took the maglia rosa, beating Coppi to third place, 1min 21sec behind. Coppi was fourth in the overall classification, again 1min 21sec behind (before the stage, they were at the same time).

Until the 11th stage, a 30 km (19 mi) team-time-trial in Modena, the general classification remained the same. Coppi’s Bianchi team won the time trial. Koblet’s Switzerland-Guerra team finished in fourth place, 26 seconds behind, and now the time gap between GC leader Koblet and Coppi, who sitting in the second place, was 55 seconds.

At the 18th stage, Koblet managed to distance himself from Coppi. Now, Coppi was 1min 59sec behind.

The next day was very hard. It was a 164 km (102 mi) mountainous stage from Auronzo di Cadore to Bolzano. There were four major passes over the route: Misurina, Falgazero, Pordoi, and Sella. Koblet attacked and opened a gap on Coppi’s favorite climb, Passo Pordoi (Pordoi Pass). Coppi managed to catch him on the Sella and counter-attacked. But Koblet was an excellent descender, he caught Coppi on the descent and the pair came into the velodrome of Bolzano together. Coppi won the sprint.

But it seemed like the Giro was over, even Coppi has admitted that he was now racing only to finish in second place. He said to Koblet that “My compliments, the Giro is yours. You are the strongest”.

Passo dello Stelvio

Coppi and Koblet made a deal: they wouldn’t attack each other in the penultimage stage, which includes the Stelvio pass. Later, Koblet would claim that Coppi had ceded the overall victory to him, in return for the stage victory – a classic bargain.

But, his Bianchi teammates (domestiques) and even the Bianchi bicycle company boss Aldo Zambrini didn’t like the deal Coppi had just made. They insisted that the Giro still could be won on the Stelvio. Coppi, on the other hand, dismissed their efforts, said Giro was over and then went to bed.

But, the next day, even before the stage, the intrigue and gamesmanship have started. Biagio Cavanna, Fausto’s cycling father and the most important influence on his cycling career, asked Coppi’s loyal domestique Ettore Milano to check on Koblet as he was registering for the stage.

He wanted to know if Koblet had “over-drunk” (had overdone the amphetamines). The amphetamine, or “la bomba”, has a lot of side effects. Maybe the worst of all is insomnia: if a rider wasn’t careful about how much of the drug he had taken, he can have a sleepless night. It can be suicidal making that mistake before a stage that hard.

Milano approached Koblet but he saw that the Swissman was wearing large, dark glasses. He had to think something, and he had to do it quickly. He persuaded a photographer to ask Koblet if he would take his glasses off for a picture.

Milano recalls “I noticed that Koblet had eyes that would scare you. I went to Fausto and said to him ‘Look, Koblet has drunk, his eyes in the back of his head'”.

Coppi wasn’t convinced. He said, “Mine are too”. Coppi was also feeling the side effects of taking too much amphetamines.

Early in the stage, Both Koblet and Coppi weren’t feeling good. Milano was watching the Swiss closely. He realized that Koblet was sweating and drinking a lot. Again, the side effects of la bomba, it makes you sweat more, it makes you thirsty. Milano told about his observations to Coppi, but Coppi replied: “I am the same”.

About four or five kilometers up to the Stelvio, as the weather getting cooler, Coppi started to feel better. He shouted to one of his domestiques, Andrea (Sandrino) Carrea, “Pappagallo (parrot), what are you doing, don’t go too hard”. This was a code for Carrea to put the hammer down.

Carrea set a red-hot pace. After he was done, there were only five riders left: Koblet, Coppi, now 39-year-old Gino Bartali, Pasquale Fornara and the young Nino Defilippis (he was just 21-year-old).

Defilippis recalls: “After Carrea was dropped, Coppi came to me and said ‘kid, can you shake up the group?’ I told him that I was cooked. I was already on my limits. But, he insisted that it would be good for my career if I did as he asked. I understood perfectly well. With what little I had left, I attacked.”

With that attack, Defilippis managed to open a gap of about 100 meters. Koblet chased him down – a big, amateurish mistake: Defilippis was no threat for the GC. Koblet caught Defilippis and passed him. But, after opened a gap about fifty meters with the young Italian, he couldn’t go any harder.

And, in a way, the deal between Coppi and Koblet was broken with the Swiss rider’s attack. Coppi counter-attacked. Defilippis recalls: “He came and past both me and Koblet like a motorbike. I’d never seen anything like it. He disappeared into the distance.”

Partway up to the Stelvio, Coppi saw his lover Giulia Locatelli, who would come to be known as “the woman in white”, because of the coat she was photographed wearing. He asked to her “Are you coming to the Bormio (the finish)?” as he passed. She said “yes”. Now Coppi was in fire.

Coppi crossed the summit alone. After the summit, the south face of Stelvio is a challenging descent. But nothing could stop Coppi. Koblet’s usual mastery of skill on the descents deserted him that day – he crashed twice and punctured once.

Coppi finished the stage 2 min 18 seconds ahead of Fornara and Koblet was 3 min 28 seconds back. Later, Defilippis said that if Koblet had just stayed on Coppi’s wheel rather than answer his attack, he would have kept the maglia rosa. According to Defilippis, Coppi thanked him later, but Koblet would never talk to him again.

Coppi and Koblet were staying at the same hotel that evening and even crossed paths in a corridor, but they didn’t speak to each other. Koblet just glared at Coppi, then entered his room and slammed the door.

Coppi won his fifth Giro. After Binda, he was the second cyclist ever to win the Giro five times. To date, only one more cyclist managed to achieve this: Eddy Merckx.

After 1953 Giro d’Italia

Next year, Koblet helped his teammate Carlo Clerici to win the Giro, and took his revenge from Coppi. Il campionissimo would never win the Giro again. 1953 edition was his last.

Both riders’ careers went downhill soon. Coppi’s last great victory was 1954 Giro di Lombardia. Koblet also never rode again at the same level. Jean Bobet, the younger brother of Lousion Bobet once said: “Koblet began to suffer in the mountains at 2,000m, then 1,500, then at 1,000 until we saw him unable to ride over the smallest hill”.

The author Olivier Dazat said photographs showed not the handsome man he had been but a rider suddenly aged, worried, and preoccupied. René de Latour wrote:

“There is a question mark about Hugo Koblet’s life, the mystery of why he was never as good again as in the 1951 Tour. After this year, his pedaling had less power. Soon after that magnificent win, Koblet was invited to Mexico to follow the national amateur tour. When he came back he was still, it seemed, the same incredibly easy pedaller. But the efficiency was partly gone. He visited specialists and took courses of treatment, but without any real success. He went to Mexico in 1951 and never came back from the land of guitars and sombreros. And nobody knows why!”

On 6 November 1964, six years after his retirement, Koblet died at 39, four days after a car crash, with speculation that his death may have been suicide. He had been profligate with his money and was in debt. He was being pursued unpaid tax and his marriage had broken up.

A witness, Émile Isler, saw Koblet driving his white Alfa Romeo at 120-140 km/h between Zürich and Esslingen. He drove past a pear tree, turned then drove back. He passed it again finally turned a third time and drove into it.

In December 1959, the president of Burkina Faso, Maurice Yaméogo, invited Coppi, Raphaël Géminiani, Jacques Anquetil, Louison Bobet, Roger Hassenforder and Henry Anglade to ride against local riders and then go hunting. Géminiani remembered:

“I slept in the same room as Coppi in a house infested by mosquitos. I’d got used to them but Coppi hadn’t. Well, when I say we ‘slept’, that’s an overstatement. It was like the safari had been brought forward several hours, except that for the moment we were hunting mosquitos. Coppi was swiping at them with a towel. Right then, of course, I had no clue of what the tragic consequences of that night would be. Ten times, twenty times, I told Fausto ‘Do what I’m doing and get your head under the sheets; they can’t bite you there'”.

Both caught malaria and fell ill when they got home. Géminiani said:

“My temperature got to 41.6 °C… I was delirious and I couldn’t stop talking. I imagined or maybe saw people all around but I didn’t recognize anyone. The doctor treated me for hepatitis, then for yellow fever, finally for typhoid”.

Geminiani was diagnosed as being infected with plasmodium falciparum, one of the more lethal strains of malaria. Géminiani recovered but Coppi died on January 2, 1960, his doctors convinced he had a bronchial complaint. They had never realized that Coppi was suffering from malaria.

Sources

- McGann, B. & C. “The Story of the Giro d’Italia, Volume One: 1909-1970”. McGann Publishing, Cherokee Village, United States, 2011.

- Fotheringham, W. “Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi”. Yellow Jersey Press, London, 2009.

- Sykes, H. “Maglia Rosa: Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia”. 1st edition. Rouleur Limited, London, 2011.

- Fausto Coppi on Wikipedia

- Hugo Koblet on Wikipedia

- 1953 Giro d’Italia on Wikipedia

- Tour de France Winner Groupsets [Year by Year, from 1937 to 2024] - July 21, 2024

- Top 18 fastest Paris-Roubaix editions - April 7, 2024

- Col de Tourmalet [Amazing photo from the 1953 Tour de France] - January 11, 2024