In 1972, On 25 October, Eddy Merckx set the Hour Record, after a great season: he started the year winning “la primavera”, Milan-San Remo, the first classic of the cycling season. He then won Liège-Bastogne-Liège, one of the five “monuments” (see notes 1), the Giro d’Italia, the Tour de France (both general classification and points classification), and another monument, Giro di Lombardia (currently “Il Lombardia“) as well as many other races.

Then he attacked the Hour Record.

The hour record for bicycles is the record for the longest distance cycled in one hour on a bicycle. The task is simple: pedal as hard as you can for one hour. But “simple” does not mean “easy”. It is widely accepted that the Hour Record is one of the most demanding sporting challenges which an athlete can undertake. It is a pure physical effort, there are no other variables such as wing, road surfaces, gradients, or other riders. It’s an absolute measure what an athlete can achieve on a bicycle.

Once Chris Boardman, who broke the Hour Record triple, has said that: “The key equation I had in my head was: how far is it to go and is my current pace sustainable? If the answer is yes then you’re not going hard enough, if the answer is no then it’s already too late, so the answer you’re looking for is maybe”. (see notes 2)

Attacking the Hour Record is also considered a great risk to a cyclist’s career: you either prove yourself or make a fool of yourself. There are no “little misses”. You cannot say “I lost by just a handful of meters”. Success or failure is so obvious, and so public since millions are watching you.

Merckx was putting his whole reputation at stake.

Eddy Merckx’s Hour Record

But he had had no other choice. The previous legends including Henri Desgrange, Lucien Petit-Breton, Fausto Coppi, Roger Rivière and Jacques Anquetil had broken the hour record at some point of their career.

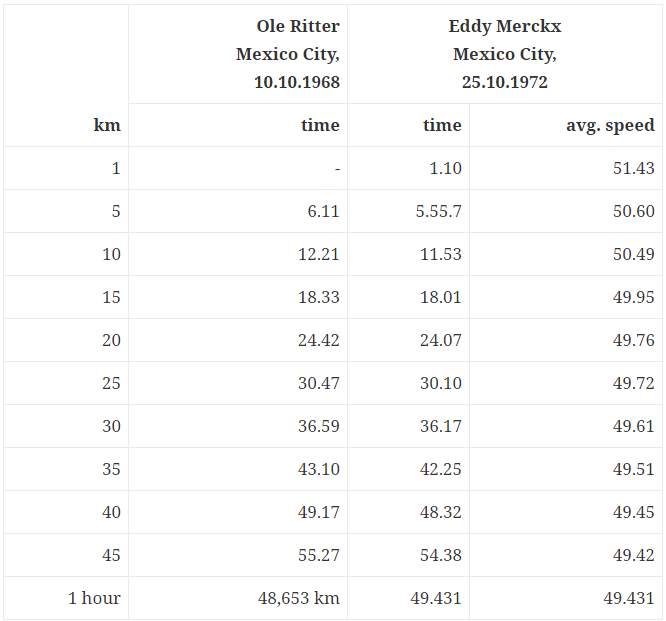

The previous hour record was standing since 10 October 1968: 48.653 km, achieved by Dane Ole Ritter in Mexico City.

His team Molteni asked Merckx to attack the record on the Vigorelli velodrome in Milan, the reason was obvious: Fausto Coppi, Roger Rivière and Jacques Anquetil had set their record there. But a visit to the Vigorelli on October 12 was disappointing. Days of heavy rain had left the track sodden and slow, unfit for the record.

Then he began to think of Mexico, the Agustín Melgar outdoor track, a 333-meter velodrome built for the 1968 Olympics – it was also the velodrome that Ritter set his record back in 1968.

The altitude of Mexico City is 2,250 meters (~7382 feet) – it has some advantages as well as disadvantages for cycling. The air is thinner, that means less air resistance. But there’s less oxygen too, means you can’t push yourself as hard as you can at the sea level. In 1969, another Belgian, Ferdinand Bracke tried to regain his record (on 30 October 1967 in Rome, 48.093 km) from Ritter in Mexico, but he failed due to poor adaptation of the thin air.

So, shortly before he went to Mexico, Merckx underwent a series of physiological tests that lasted for seven hours over two days under the expertise of professor Paolo Cerretelli, head of the third Chair in Human Physiology at the University of Milan. They put him under some stress tests on the bike rollers, making breathing a mixture of thin air would be in Mexico City. In the intervals between each test, they also controlled the return to standard heart rate, what is called recovery time.

At the end of the evidence, the verdict was unanimous from the clinical point of view, they concluded Eddy Merckx could be considered a phenomenon. First of all, he had a very high maximum absolute power. Second, in the unit time, Merckx could consume up to five gallons of oxygen, while a normal individual could consume a maximum of three. The test data showed that Merckx’s heart, in every beat, could pump twice as much blood as a normal individual.

Famous frame builder (still one of the most important framebuilders in the world) Ernesto Colnago had constructed Merckx a special road bike for the record attempt, with the same measurements as his track bike. The machine weighed just 5.9 kg. At his first race with the bike (the Giro del Piemonte), on 9 September (see notes 3), he attacked sixty kilometers from the finish not to win, but to practice riding flat out in the same position he would use for the Hour (see notes 4) (He also won the race against the giants like Felice Gimondi, Franco Bitossi, Gianni Motta and Wladimiro Panizza).

In an interview published in Sosenka.cz (see notes 5), Ernesto Colnago said that: “…in those days, the tubing was 6/10 to 4/10 wall thickness. A guy like Merckx, who weighed 72kg., 1m85cm high with incredible power, well, to build a superlight bicycle for someone like that took a lot of courage. I lightened everything; the cranks, drilled out the chain because we wanted the lightest material and well, you couldn’t buy a Regina Extra chain with holes drilled in it! So the bike ended up weighing just over 5.5kg.”

“Do you realize that the tubular tires we used, the Clement number 1 Pista, weighed 90 gr. for the front and 110 gr. for the rear! No one else could have put this bike together. For example, no one in Italy could weld titanium, so I went to Pino Morroni in Detroit, America to weld the special lightweight titanium stem for Merckx’s Hour Record bicycle.”

In the first day, after training on the Mexico City velodrome, Merckx decided that track was fast, so he opted a higher gear, 52×14, rather than 52×15. But the next two days were rainy. Finally, by the day tree, the sun showed its face. By the morning on October 25, he breakfasted before seven, and his pedals started to turn for the record at 08:46 am.

There were a lot of spectators, more than two thousand, including King Leopold of Belgium, and princesses Liliane, Esmeralda and Marie-Christine.

The cycling legend, one of the previous record holders, 5-time Tour de France winner Jacques Anquetil had warned him about an overly rapid start that would leave him weak late in the ride. But, being Merckx, he started fast – really fast: he covered the first kilometer in 1 minute 9.97 seconds – back then good enough to win a World Championship medal over the distance! Maybe he even dreamed of pushing the record over 50 km.

The second kilometer was even faster: 1 minute 9.84 seconds. He covered 5 kilometers in 5 minutes 55.7 seconds – he was already 14 seconds up on Ritter’s record to this point.

The crisis came, between 42nd and 48th minutes: his progress against Ritter slowed dramatically. Giorgio Albani, who had the job of standing where Merckx actually was when the bell was rung, recalls: “It was ugly, I had been walking forward, but I went from a lap and three quarters ahead, then just a lap ahead. Merckx said ‘I am dead’, I told him to calm down, and said ‘if you’re traveling at forty-nine and a half kilometers per hour you must be alive.'” (see notes 4)

The last kilometer is covered in one minute and 11.76 seconds, the final complete lap (the 148th) in 24 seconds (see notes 4). The result: he broke the record by 788 meters, the biggest margin of modern times (biggest since 1912).

Ole Ritter and Eddy Merckx split times

After beating the hour record, Eddy Merckx, the greatest cyclist of all time, has said that: “I will never start one again”.

He explained:

“Throughout this hour, the longest of my career, I never knew a moment of weakness, but the effort needed was never easy. It’s not possible to compare the Hour with a time trial on the road. Here it’s not possible to ease up, to change gears or the rhythm.”

“The Hour Record demands a total effort, permanent and intense, one that’s not possible to compare to any other. I will never try it again. There are those who told me that if I came here to Mexico I wouldn’t feel the pedals. I assure you, I could feel the pedals! Nevertheless, I don’t regret this choice.”

“I don’t think I could ever improve on this record. Yet I am convinced that one day my record will be beaten. That is the law of the sport. But to beat it, it will be necessary to push a bigger gear. My 52X14 was plenty big for me. For five or six kilometers it didn’t pose a problem, but for a whole hour it was very much otherwise.”

NOTES and SOURCES

- The Five Monuments of Cycling are generally considered to be the oldest and most prestigious one-day events on the calendar, after the World Championship Road Race.

- Milan-San Remo (Italy) – the first true Classic of the year, its Italian name is La Primavera (the spring), this race is held in late March. First run in 1907.

- Tour of Flanders (Belgium) – also known as the Ronde van Vlaanderen, the first of the “Cobbled Classics”, is raced in early April. First held in 1913.

- Paris-Roubaix (France) – the “Queen of the Classics” or l’Enfer du Nord (“Hell of the North”) is traditionally one week after the Tour of Flanders, and was first raced in 1896. See Top 15 fastest Paris-Roubaix editions

- Liège-Bastogne-Liège (Belgium) – late April. La Doyenne, the oldest Classic, was first held in 1892 as an amateur event; a professional edition followed in 1894.

- Giro di Lombardia (today Il Lombardia, Italy) – also known as the “Race of the Falling Leaves”, was held in October. Initially called the Milano-Milano in 1905, it became the Giro di Lombardia in 1907 and Il Lombardia in 2012 along with a new, earlier date at the end of September.

- Chris Boardman’s five top tips for your first ten-mile time trial

- The Giro del Piemonte, since 2009 also known as Gran Piemonte, is a semi-classic European bicycle race held in the Apennine Mountains, Italy. The race first took place in 1906. Since 2005, the race has been organized as a 1.HC event on the UCI Europe Tour. It is usually held a few days before the more important race Giro di Lombardia (currently Il Lombardia). In 2007, the race was not ridden because of sponsorship problems, but in 2008 it was back again. The 2013 edition was again canceled due to financial problems.

- “Eddy Merckx: Half Man, Half Bike”; Fotheringham, W.; Yellow Jersey Press; London, 2012.

- Ondřej Sosenka (born on December 9, 1975, in Prague) is a Czech professional cyclist who last rode for the UCI Professional Continental team PSK Whirlpool-Author. He won the Peace Race in 2002. He broke the nine-year-old UCI hour record on July 19, 2005, in Moscow, Russia, riding 49.7 kilometers (30.9 mi) in one hour.

- UCI Elite Men Road Race World Champions: The Complete List [1927-2025] - September 28, 2025

- What Is Zone 2 In Cycling? - September 12, 2025

- The Turkish Flag at the Tour de France: Who’s Waving It at the Finish Line? - July 30, 2025

2 replies on “Eddy Merckx’s Hour Record in 1972 [Video]”

You can view the bike at Eddie Merckx tube station in Brussels. It is a small station – just two platforms. I was astounded to discover it there. The frame bears the makers name “windsor” which is or was a Mexican brand. Colnago was, understandably, livid. I wonder if there was a sponsorship deal going on. I live in Brussels and like everyone here I regard Eddie Merckx as the God of cycling. He is by all accounts a very nice man.

Hi Robert,

Thanks for the comment!