I’ve inspired by GCN’s video titled “Top 10 iconic road bikes in racing history” while writing this post. I made some changes, excluded some of Daniel Lloyd’s choices, and extended the list by including a few bikes. Here are the top 12 iconic bikes in cycling history (IMHO, of course).

Here is my list of “top 12 iconic bikes in cycling history” below:

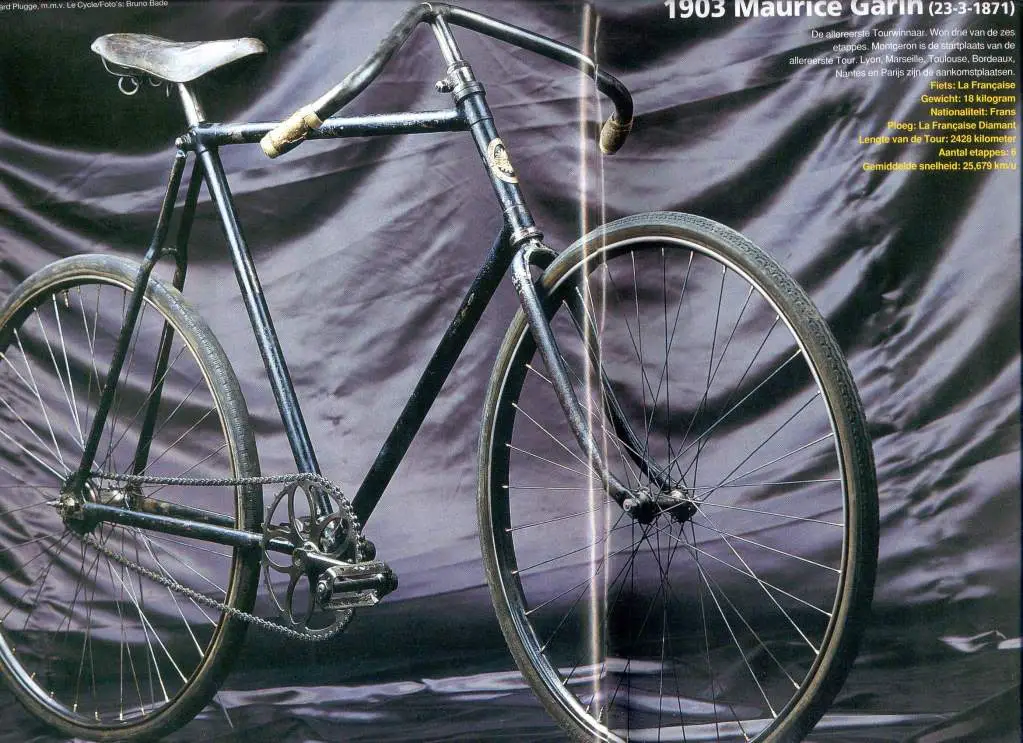

12. Maurice Garin’s La Française – the first bicycle to win the Tour de France

Maurice Garin (3 March 1871, Arvier, Aosta Valley, Italy – 19 February 1957, Lens or Haute-Savoie, France) was the overall winner of the first Tour de France (1903).

Garin’s La Française bike was weighing 18kg (the UCI limit is 6.8kg and all the bikes are around 6.8-7 kg now). Despite the really long stages, a heavy bike with no gears, and the bad roads, Garin’s average speed was 25.679 kph. He was riding for the “La Française Diamant” team.

11. Mario Cipollini’s Cannondale CAAD series bikes

In the 1990s, the Italian Saeco was a top-level European team, with the world’s fastest sprinter Mario Cipollini on the squad. Cipollini raced an “R4000” model (CAAD3) in the 1997 season. The team was famous for Mario Cipollini’s sprint train and his antics.

One of their most memorable moments was Cipollini’s 4 consecutive stage wins in the 1999 Tour de France. The image of Mario Cipollini approaching the TV camera right after a win to say, “Cannondale makes the best bikes!” propelled Cannondale’s popularity among road racers.

The Saeco team is known for its pranks and antics. Cipollini’s antics are legendary, including showing up to the stage start at the Tour de France dressed in a Julius Caesar-inspired toga complete with an olive wreath, riding on a carriage pulled by his teammates on bicycles.

More recently, the entire Saeco team raced a stage of the 2003 Tour de France wearing a Legalize my Cannondale chain gang cycling kit to protest the UCI’s lower bound on bike weight which means that their six13 prototype team bikes were underweight and required the installation of additional weight.

10. Miguel Indurain’s Pinarello Sword (Pinarello Espada)

Pinarello Sword is a conceptional bike that took 5-time Tour de France winner Miguel Indurain to some of his most impressive time-trial wins. This bike didn’t last long thanks to the UCI, but it has made a lasting impression.

9. Chris Boardman’s Lotus 108

The Lotus Type 108 (originally known as LotusSport Pursuit Bicycle) is an Olympic individual pursuit bicycle. The revolutionary frame is an advanced aerofoil cross-section using a carbon composite monocoque.

The use of monocoque frames for bikes is not new, but their development was improved through the work of Norfolk-based designer Mike Burrows (who later designed Giant TCR, the first sloping geometry – or “compact” road bike).

Burrows’ design was initially rejected by British cycling manufacturers. However, it was to be received more enthusiastically by the British Cycling Federation. The design was considered illegal by the UCI. Therefore the project was prematurely shelved in 1987.

In 1990, the UCI revoked the ban on monocoque frames. Shortly after this, Lotus Engineering became involved in the project through a friend of Burrows who took his design to the Lotus factory. The potential was evident and Lotus’ knowledge and aptitude at using carbon fiber techniques allowed the design to finally realize its potential.

By February 1992, Lotus Engineering had acquired the rights and marketed the bike as the LotusSport Bike. In addition, the design was modified and perfected through a series of wind tunnel tests, by the Lotus aerodynamics specialist Richard Hill. The success of this was emphasized when Bryan Steel was able to shave five seconds off his time for the two-kilometer pursuit at an international race meeting in Leicester.

The profile of Lotus and Burrows was raised at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. A new world record of 4 minutes 24.496 seconds was established as well as Chris Boardman winning the 4000m pursuit, catching World Champion Jens Lehmann in the final.

8. Pinarello Dogma 2012/2013

In 2013 Tour de France, Chris Froome of Team Sky won the yellow jersey, and Nairo Quintana of the Movistar team won both polka dot jersey of the KOM (King of the mountains) and white jersey of “the best young rider” classifications on Pinarello Dogma bikes. And In the UCI Worlds, Portugal’s (he was a Movistar rider, too) Rui Costa won the road race gold medal, riding a Pinarello Dogma.

Also in 2012, Froome’s teammate Bradley Wiggins won the Tour de France, while Froome finished in second. The Pinarello Dogma is already an iconic bike.

7. Roger De Vlaeminck’s Gios Torino

Brooklyn Chewing Gum was an Italian cycling team during the 1970s and early 80s. It was a classics team and featured many of the great classic riders such as Roger de Vlaeminck, who won four Paris–Roubaix.

The famous Italian frame builder Aldo Gios built Gios Torino’s that carried Roger de Vlaeminck to many classic victories including Paris-Roubaix and Milan-San Remo.

A documentary called A Sunday in Hell features the team during the 1976 Paris-Roubaix.

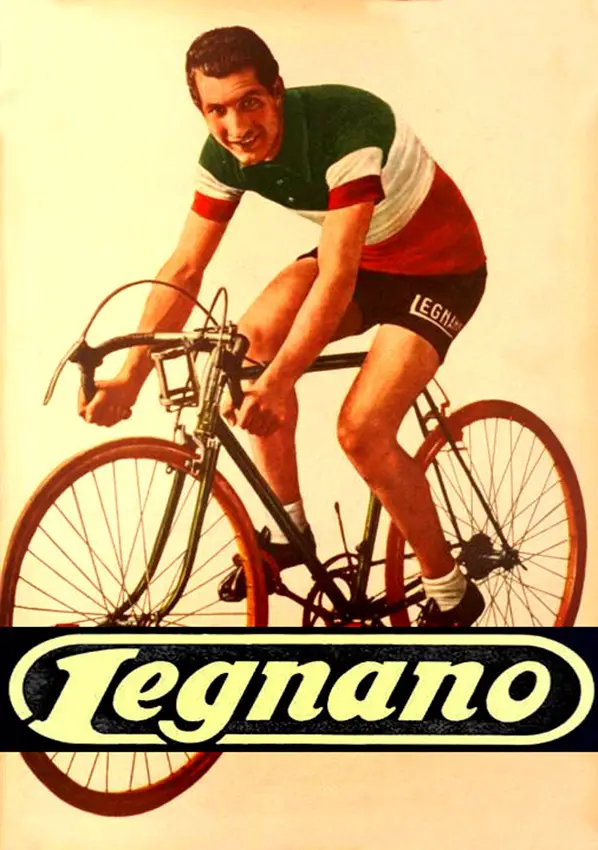

6. Gino Bartali’s Legnano

The history of Italian bicycles starts with the “L” of Legnano. Few if any marques can boast a legacy of success in the competition thanks to champions like Alfredo Binda, Giovanni Brunero, Learco Guerra, Gino Bartali, Fausto Coppi, and Ercole Baldini.

The Legnano racing bicycles were initially painted blue, then a light olive green, before taking on their unique metallic “lizard green” color at the end of the ’30s that would also serve to define the brand. Legnano frames also have a feature that makes them immediately recognizable, placing the seat post binder bolt immediately below the top tube and just in front of the seat tube.

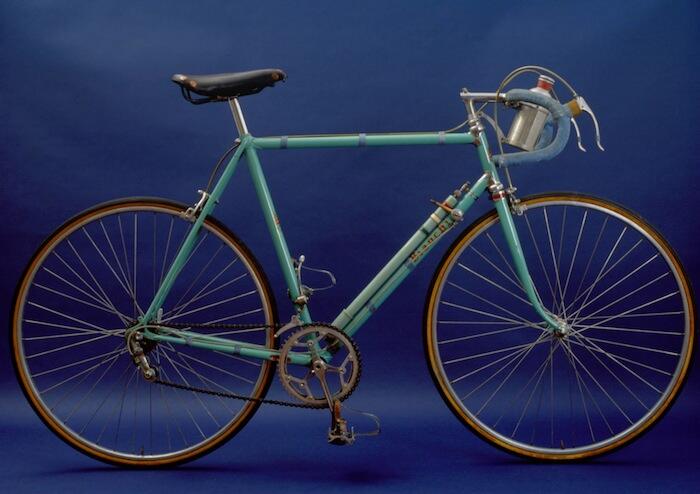

5. Fausto Coppi’s Bianchi

F.I.V. Edoardo Bianchi S.p.A is the world’s oldest bicycle-making company still in existence, having pioneered the use of equal-sized wheels with pneumatic rubber tires in 1885. It was founded in Italy in 1885. It produced cars and commercial vehicles from 1900 to 1939 as Autobianchi, though that business was sold to Fiat; and motorcycles from 1897 to 1967. Bianchi has been associated for 50 years with the 5-time Giro d’Italia ad twice Tour de France winner, Fausto Coppi.

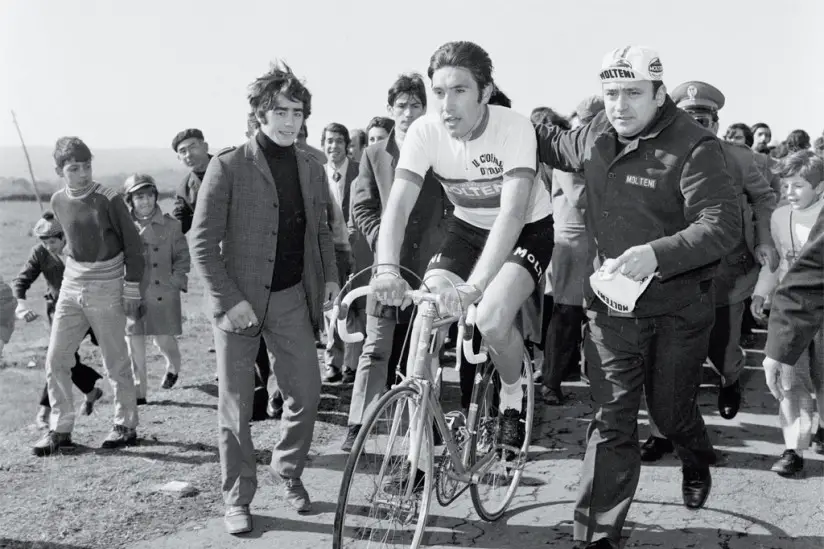

4. Eddy Merckx bikes

It was Ernesto Colnago’s idea to create a bicycle with the ace of clubs logo and Eddy Merckx’s name. In one move, Colnago started the custom bicycle boom.

Merckx used De Rosa bikes, with his name painted on the frame too, in later years of his career.

Related: Eddy Merckx’s Hour Record (video)

3. Greg LeMond’s 1989 Bottecchia

Bottecchia is a historical bicycle company that started as a small cyclery of Carnielli and was improved in 1924 by Ottavio Bottecchia, the first Italian Tour de France winner (1924, 1925). A new company with the new name “Bottecchia” was born after the death of Ottavio Bottecchia in 1926. In 1940 the workforce of Bottecchia was 100 people and the company became an outstanding race firm with the historical name of Ottavio Bottecchia and under the management of the Carnielli family.

Greg LeMond, triple Tour de France winner and twice UCI world champion, won 1989 Tour de France on an extraordinary Bottecchia, with the narrowest margin in its history: eight seconds, “the most astonishing victory in Tour de France history”.

Maybe the most important feature of the bike, the most notable first use of the aerobars: In 1989, the Swiss bicycle manufacturer Scott introduced one of the most significant product innovations in the history of cycling – the clip-on aerodynamic handlebar. The handlebar was strategically utilized by Greg LeMond when he beat Laurent Fignon by nearly a minute in the 24.5km final time trial.

2. Colnago Mapei

Colnago’s Mapei bike won the Vuelta a España when still a prototype and the reigned pro cycling for nearly a decade. It reached truly iconic status when painted in team Mapei colors and handing out crushing defeats in countless monumental classics of cycling.

1. Graeme Obree’s “Old Faithful”

While Chris Boardman and Mike Burrows were working on the Lotus 108 project, in Scotland, another young, unemployed British amateur racer had been pottering away in the workshop of a friend’s bike store.

It was Graeme Obree.

Nicknamed The Flying Scotsman, Graeme Obree is a Scottish racing cyclist who twice broke the world hour record, on July 1993 and April 1994, and was the individual pursuit world champion in 1993 and 1995. He was known for his unusual riding positions. He joined a professional team in France but was fired before his first race.

“Graeme was an eccentric guy who brought a completely different position to riding,” said Boardman, unaware at the time that Obree’s eccentricities would later be diagnosed as bipolar disorder.

“He was a real oddity and from a personal perspective, he was the only person in my early career that, pre-Olympic Games, could still beat me in a time trial when I was on top form. When I look back, I realize that moved me on. Without him, I would have stayed where I was because the level of commitment got me the rewards that I wanted. But only by somebody being there to push me did I move forward again. So he was instrumental, ironically, in me winning the Olympic Games and everything else.”

He built the “Old Faithful”, which included parts from a washing machine, to break the hour record.

His life and exploits have been dramatized in the film The Flying Scotsman. Obree has created some radical innovations in bicycle design but has had problems with the cycling authorities banning the riding positions his designs required.

In March 2010, Obree was inducted into the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame.

Obree had built frames for his bike shop and made another for his record attempt. Instead of traditional dropped handlebars, it had straight bars like those of a mountain bike. He placed them closer to the saddle than usual and rode with the bars under his chest, his elbows bent and tucked into his sides like those of a skier.

Watching a washing machine spin at 1,200 rpm led him to take the bearings, which he assumed must be of superior quality, and fit them to his bike. Obree later regretted admitting to the bearings experiment, because journalists referred to that before his achievements and other innovations.

Obree called his bike “Old Faithful”. It has a narrow bottom bracket, around which the cranks revolve, to bring his legs closer together, as he thought this is the “natural” position. As shown in the film, he thought a tread of “one banana” would be ideal. The bike has no top tube so that his knees did not hit the frame.

The chainstays are not horizontal so that the cranks can pass with a narrow bottom bracket. The fork had only one blade, carefully shaped to be as narrow as possible. A French writer who tried it said the narrow handlebars made it hard to accelerate the machine in a straight line but, once it was at speed, he could hold the bars and get into Obree’s tucked style.

“At a high enough speed, [I could] tuck in my arms. And, above all, get in a very forward position on the bike, on the peak of the saddle. The Obree position isn’t advantageous simply aerodynamically, it also allows, by pushing the point of pedaling towards the rear, to benefit from greater pressure while remaining in the saddle.”

“You soon get an impression of speed, all the greater because you’ve got practically nothing [deux fois rien] between your hands. Two other things I noticed after a few hundred meters: I certainly didn’t have the impression of turning 53 × 13, and the Obree position is no obstruction to breathing. But I wasn’t pedaling at 55km/h, 100 turns of the pedals a minute, yet my arms already hurt.”

Obree attacked Francesco Moser’s record, on 16 July 1993, at the Vikingskipet velodrome in Norway. He failed by nearly a kilometer. He had booked the track for 24 hours and decided to come back the next day. The writer Nicholas Roe said:

To stop his aching body from seizing up, Obree then took the unusual measure of drinking pint upon pint of water so that he had to wake up to go to the lavatory every couple of hours through the night. Each time he got up, he stretched his muscles. On the next weary day, he was up and out with minutes, at the deserted velodrome by 7:55 am and on the track ready to start just five minutes after that. He had barely slept. He had punished his body hugely the previous day. Surely this was a waste of time?

Obree said:

I was Butch Cassidy in terms of swagger. I didn’t want any negativity. This was a blitzkrieg. I’m going in there. Let me do it. I’m not going to be the timorous guy from Scotland. That’s what the difference was. Purely mental state. The day before, I had been a mouse. Now I was a lion.

Obree set a new record of 51.596 kilometers, beating Moser’s record of 51.151 kilometers by 445 meters.

Obree’s triumph lasted less than a week. On 23 July, the British Olympic champion, Chris Boardman broke Obree’s record by 674 meters, riding 52.270 km at Bordeaux during the rest day of the Tour de France.

His bike had a carbon monocoque frame, carbon wheels, and a triathlon handlebar. Their rivalry grew: a few months later Obree knocked Boardman out of the world championship pursuit to take the title himself.

Francesco Moser, whose record Obree had beaten, adopted Obree’s riding position—adding a chest pad—and established not an outright world record but a veterans’ record of 51.84 kilometers. He did it on 15 January 1994, riding in the thin air of Mexico City as he had for his outright record, whereas Obree and Boardman had ridden at close to sea level.

Obree retook the record on 19 April 1994, using the track that Boardman had used at Bordeaux. He rode 52.713 kilometers. Miguel Indurain has beaten that distance on 2 September 1994.

The world governing body, the Union Cycliste Internationale, grew concerned that changes to bicycles were making a disproportionate improvement to track records. Among other measures, it banned his riding position: he did not find out until one hour before he began the world championship pursuit in Italy. Judges disqualified him when he refused to comply.

Obree developed another riding position, the “Superman” style, his arms fully extended in front, and he won the individual pursuit at the world championships with this and Old Faithful in 1995. That position was also banned. The original bike is on display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, while two near-replicas built for use in the Flying Scotsman film are displayed in the Riverside Transport Museum in Glasgow.

Sources

- Global Cycling Network youtube channel – Top 10 Iconic Road Bikes video

- Saeco team on Wikipedia

- Lotus 108 on Wikipedia

- 50 stunning Olympic moments No43: Chris Boardman’s golden Barcelona on The Guardian

- Bianchi on Wikipedia

- Colnago.com

- Graeme Obree on Wikipedia

- UCI Elite Men Road Race World Champions: The Complete List [1927-2025] - September 28, 2025

- What Is Zone 2 In Cycling? - September 12, 2025

- The Turkish Flag at the Tour de France: Who’s Waving It at the Finish Line? - July 30, 2025

4 replies on “Top 12 iconic bikes in cycling history”

Great story, thanks. But there is one more and most important to all of them is Cinelli Laser.

İt won about 50 gold medal. This bike change the entire design approch to geometry etc.

http://cinellionly.blogspot.com/search/label/Laser%20Crono%20Squadra

fyi…that “Ernesto Colnago, Mapei 1994” is actually from 2002, the year after Oscar Freire won the Worlds for the 2nd time while riding for Mapei…that’s a B-stay C40 in a special color scheme to commemorate that victory.

Yes! Thanks for the correction, fixed…

Bartali won the Tour de France in 1948 on a Legnano with Campagnolo Cambio Corsa rear changer and occasionally a Simplex Competition front changer. He didn’t win it again. The 1950 bike is a Bartali. Production Cicli Bartali were initially built by Santamaria in Novi Ligure