Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali: two cycling legends of Italy. The rivalry between them is perhaps the most famous sporting duel in history. It has been started during World War II and continued afterward.

In December 2012, RCS Sport, the organizer of the Giro d’Italia, has put together 100 journalists to rate the greatest moments of the race’s 103-year history. The fifth question was “Which are the biggest sporting rivalries in the Giro d’Italia?”, and the obvious answer was: “The rivalry between Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali.”

The Background

By the beginning of the 1940s, Gino Bartali was already an Italian cycling hero.

In 1935, when he was only 20 years old, he won a stage of the Giro d’Italia and was Gran Premio della Montagna or GPM (KOM – King of the Mountains equivalent of Giro d’Italia), the first of seven times he won the title in the Giro.

He won the 1936 and 1937 Giri d’Italia, while skipping the 1938 edition of his home grand tour to win the Tour de France that year in a commanding fashion (he also won the mountains classification). He won the race 18 minutes 27 seconds ahead of the second finisher Félicien Vervaecke of Belgium (the race was contested by national teams).

Along with the grand tours, before the Giro d’Italia 1940 starts, Bartali also won Coppa Bernocchi (1935), National Road Race Championships (1935, 1937), Giro di Lombardia (1936, 1939), Giro del Lazio (1937), Giro del Piemonte (1937, 1939), Tre Valli Varesine (1938) Milan-San Remo (1939, 1940) and Giro di Toscana (1939, 1940).

Battle of the Giants starts: 1940 Giro d’Italia

The legendary Gino Bartali and his “greens” in the Legnano team had been Fausto Coppi’s heroes in his amateur days.

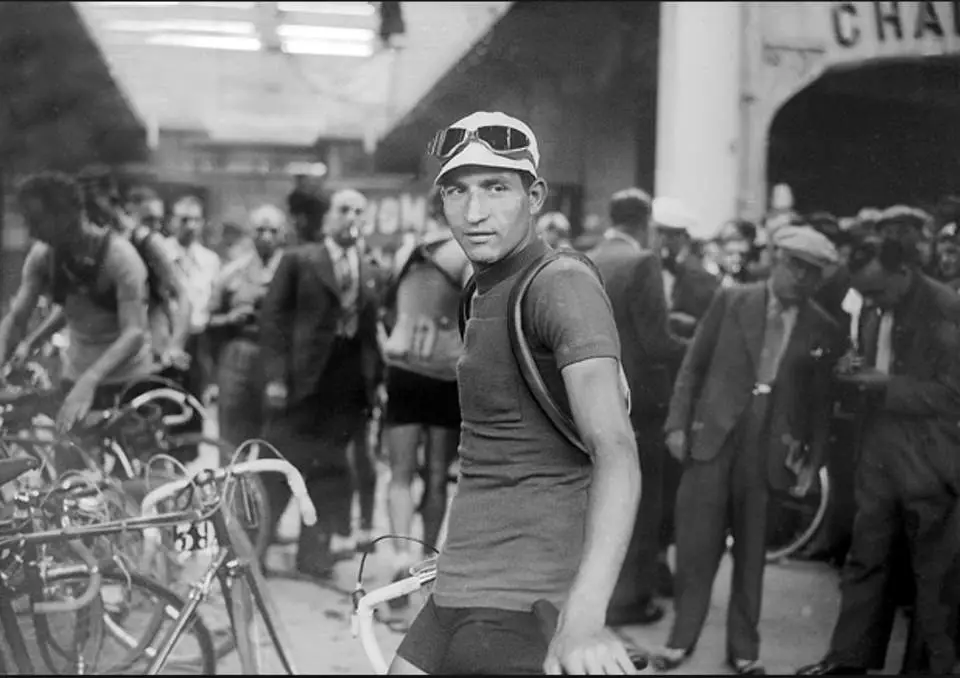

At the beginning of 1940, the 20-year-old Fausto Coppi turned professional and signed with Legnano for 700 Italian Lire a month.

Supported by his high-powered Legnano team, Gino Bartali was the biggest favorite of 1940 Giro. But during the second stage between Turin and Genoa, he hit a dog, crashed heavily, and dislocated his elbow. His gregario (domestique) Coppi also crashed twice, but continued on and stayed with the leaders, didn’t wait for Bartali.

Related: Watch Coppi, he’s like Binda

The doctors were alarmed by the severity of Bartali’s injuries and told him to abandon, but he refused and rode to the finish accompanied by Vicini and Bizzi, losing 5 minutes 15 seconds.

At the end of the stage, Osvaldo Bailo (Gerbi Team) was now the race leader with Coppi’s teammate Pierino Favalli in second place and Coppi third, trailing Bailo by only 11 seconds.

Before stage 11, Coppi was still lying in third place, 2:42 behind the race leader Enrico Mollo (Olympia). Bartali was still recovering. Stage eleven had three major passes, including the particularly tough Abetone ascent north of Pistoia. It was on the slopes of Abetone, in snow, cold rain, thunder, and lightning, that the pattern for the rest of the race was set.

Coppi, an unknown… Fausto, an even more unknown name…

Coppi had been told by Legnano Team Manager Eberardo Pavesi (see notes 1) to ride his own race and escaped alone. Bartali had a mechanical problem and stopped. At the same time, the young Fausto attacked.

Once Coppi had flown, the older man had no choice but to remain with the other team leaders as they spent their energy chasing his teammate, if they caught Coppi, it would be his turn to attack; a classic racing tactique.

Orio Vergani wrote in Corriere della Sera:

“…on the road lashed by the frozen, cutting rain. People at the roadsides huddled under umbrellas, trying to read the number stamped on his frame, looked for his name in the paper that corresponded to the number… Coppi, an unknown… Fausto, an even more unknown name…”

Another commentator recalled spectators yelling “Isn’t that the skinny guy who rides for the green rats?”

By the end of stage 11, Coppi took over the maglia rosa.

Bartali was really unhappy about this Giro and wanted to quit. Pavesi knew that his team leader was only twenty years old and the most challenging part of the Giro, the Dolomites, was yet to come. He counseled Bartali to stay in the race and be ready to pick up the pieces should Coppi fade.

Coppi rode well the next four stages, but his crisis took place when Giro reached the Dolomites on stage sixteen. There Coppi had apparently stuffed himself with chicken-salad sandwiches before the start of the stage and when the road started to tilt skyward, both Vicini and the chicken sandwiches attacked.

Coppi started to have stomach problems. Whether it was nerves or food poisoning in an era before universal refrigeration, Coppi was in crisis. By the time they confronted the second mountain pass, his stomach could take it no more. He had to get off his bike to vomit, forcing him to watch the pack and the team cars leave him behind.

Bartali had been chasing the peloton after flatting and came across the miserable Coppi, who was still stopped by the side of the road. He started rescuing his teammate with a pep talk, telling him that the race could still be won. He gave Coppi some of his own water, talked him into getting back on his bike, and got him riding back into the race.

Vicini won the stage and Mollo followed in just shy of three minutes later. But with Bartali’s help, Coppi had saved his lead in the general classification, finishing only four seconds behind Mollo. Bartali was a further three minutes back, but his vital work as ad hoc coach and soigneur had been done. The day was saved.

The pink jersey was saved, but the next day was the tappone (the race’s hardest and most demanding stage, always in the high mountains), only 110 km long, but included three massive climbs: the Falzarego, Pordoi, and Sella passes. With a rest day and then three flat stages before the finish, this was where the race would be decided.

Pavesi famously told the owner of the café at the top of the Falzarego to have bottles of coffee ready and give them to the first two riders to crest the pass. The café owner asked who those riders would be. Pavesi told him that one would be wearing the Italian Champion’s tricolore (Bartali) and the other would be wearing the maglia rosa (Coppi). So superior were the two Legnano riders that Pavesi’s prediction came true.

Over the next kilometers, Coppi flatted at least twice and Bartali waited for him. But on the Sella, when Bartali flatted Coppi started to take off. Pavesi stopped the impetuous youngster, telling him that certain proprieties had to be observed. Chastened, Coppi waited for his generous team captain.

During the rest of the stage, Coppi bonked, even Bartali was pacing him “with patience, even with love”, as the young man struggled to hang on to his wheel. At one point Coppi stopped, and Bartali took a handful of snow and rubbed it on Coppi’s forehead, then he dropped it onto the nape of his neck.

On the descent to the finish in the little town of Ortisei, Coppi missed a turning and punctured, it was Bartali who gave him his wheel.

There were three more stages but Coppi had the race in the bag. At 20 years 8 months 18 days, he was and remains the youngest rider to win the Giro d’Italia.

It was also the first act in what would become Italy’s greatest sporting rivalry. Bartali made it clear: “You can rest but don’t have too many illusions: give it a year and I’ll put things back how they should be”, he told Coppi.

But they had to wait six years for the Giro to be run again.

World War II

During the rest of 1940 and 1941, the rivalry between Coppi and Bartali became more intense, even though the two cyclists were still racing in the colors of Legnano. In the 1940 Giro di Lombardia, Coppi was close to winning, he escaped from an early break, but his stomach played up again, and Bartali did overtake him, won the race.

1941 started brightly for Coppi, he won the single-day spring events Giro dell’Emilia, Giro del Veneto, Tre Valli Varesine, and Giro della Provincia di Milano. He had recruited at least one Legnano teammate to work for him instead of Bartali: Mario Ricci.

Coppi also won the 1941 Giro della Toscana, he rode the final 40 miles alone and finished three minutes ahead of Bartali. In only his second season as a professional, he seemed stronger than his master.

Then World War II stepped into everyone’s lives. Both Coppi and Bartali played their parts in the war, but this is another story.

Post War Years, 1946 Milan-San Remo

On 22 November 1945, Coppi married a girl named Bruna. He was still a poor man, there was no money to deck the church with flowers. Bartali had overlooked their rivalry and rigged a win for Coppi in a criterium so he could take home a bouquet or two.

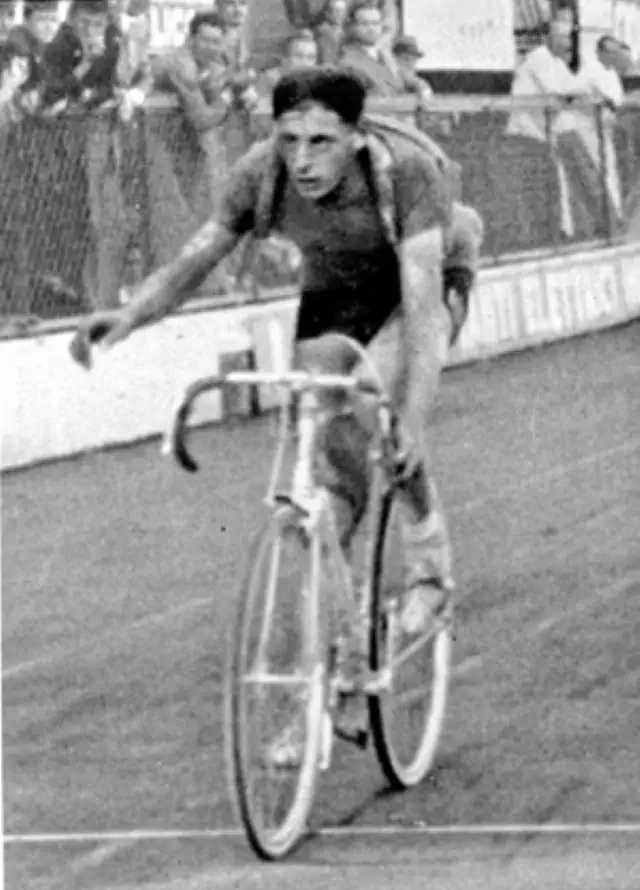

Coppi signed with Bianchi team, the main rival of Bartali’s Legnano team. In 1946 Milan-San Remo (the first classic race after the war) Coppi took a crushing victory. He remained alone in the lead all the way to San Remo, for 147 kilometers of the 290-odd that make up the race. This was the biggest winning margin of his career in a single-day event: he was 14 minutes ahead of the second-finisher Frenchman Lucien Teisseire. Bartali was 24 minutes behind.

Giro d’Italia 1946

At stage five, Coppi crashed and broke a rib. But he effectively lost the race on the stage to Napoli (Naples), nine days in, when he had to stop to adjust a defective brake.

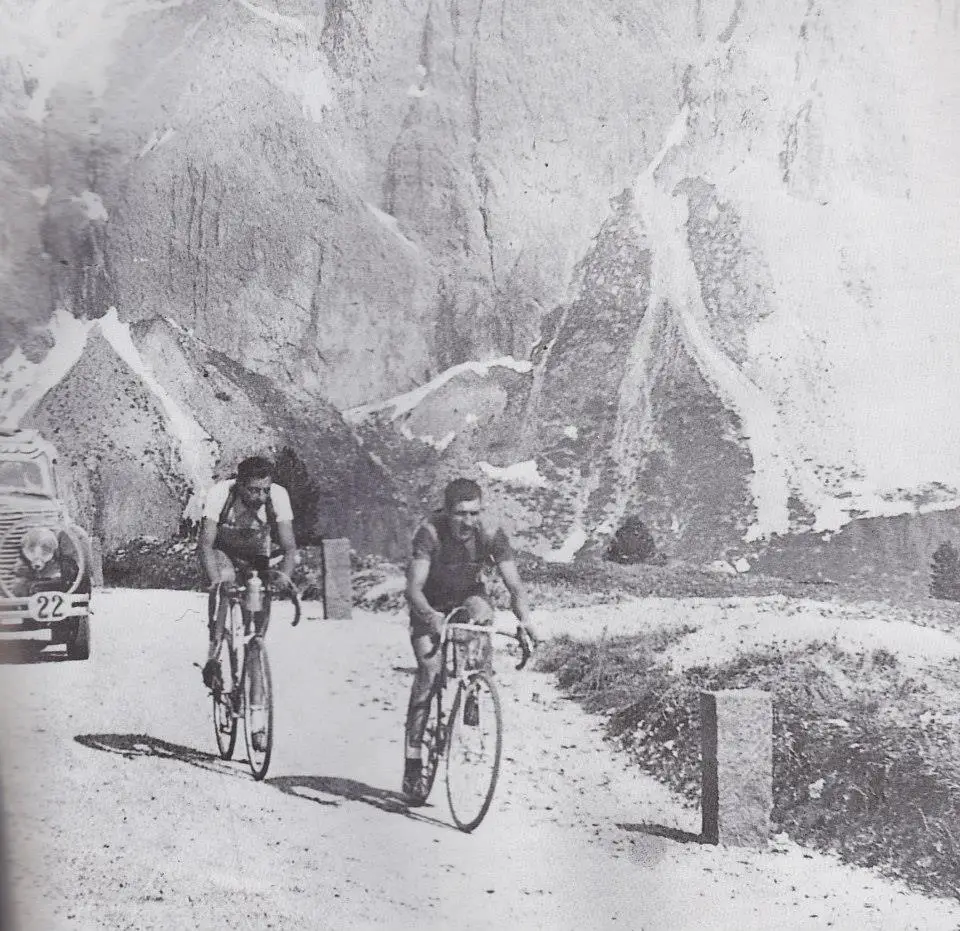

On the Dolomites, Coppi was powerful. He and Bartali rode away from the field in stage fifteen with its crossing of the Passo della Mauria. Coppi won the stage with Bartali finishing with him at the same time. Race leader Vito Ortelli came in 1:34 seconds later, giving Bartali the lead by 10 seconds.

Coppi won again when he went away alone on the Falzarego pass in stage sixteen. With 35 kilometers to go Coppi had a five-minute gap on Bartali, making Coppi virtual Pink Jersey. Bartali had been chasing Coppi, but only with the greatest difficulty, and looked to be running out of steam.

Team director Pavesi told Bartali to wait for teammate Aldo Bini. Bini, who had been dropped long ago, mysteriously closed the gap up to Bartali at that perfect moment.

How? Did Pavesi know that Bini had somehow found new energy that made him capable of riding in the Dolomites as fast or faster than Fausto Coppi? In any case, with the help of Bini, Bartali was able to contain the Coppi threat to his leadership, losing only 72 seconds by the end of the stage.

Coppi couldn’t find enough magic to overtake and drop Bartali in the seventeenth stage, In fact, Bartali was first over the Passo Rolle, but Coppi finished the stage nine seconds ahead of Bartali when they rolled into Trent after six hours of racing.

While the day may not have given Coppi the lead over Bartali, who was clearly riding in a state of grace, with time bonuses Coppi was now sitting in second place, only 47 seconds behind Bartali. The next three stages had no effect on the top classification standings. Bartali was the winner in Milan.

Coppi-Bartali rivalry reached its never-ending peak with that Giro. It has lasted until Bartali retired from professional cycling and Coppi’s strength faded.

During a stage in Tuscany, Bartali spotted Coppi dropped a bottle containing a strange green liquid.

At the finish he didn’t even wait to get a shower: “I took the car and retraced my steps. I needed that bottle.” The next day, with the help of a chambermaid, he inspected Coppi’s room, checked everything: medicines, scent bottles, flasks, test tubes, even suppositories.

However, there was nothing suspicious, apart from Bartali himself. He got the green liquid from the original bottle analyzed, and found it contained a “common pick-me-up, made in France”. To make sure he wasn’t missing anything, he ordered a case.

Coppi complained publicly for Aldo Bini helped Bartali, but the day before, he had reached an agreement with Bartali to combine forces against Vito Ortelli. On another Dolomite stage, when Bartali was sick, it was Coppi who got off his bike, poured water over to clean him up, and offered him encouragement. It was pure theater, and it was just the beginning of the show.

By the end of the 1940s, it was impossible to mention one without the other.

Coppi e Bartali, Bartali e Coppi: A Soap Opera between two giants

Sports fans likes duels: Ali vs Frasier, Senna vs Prost, Schumacher vs Hakkinen, Federer vs Nadal… All sports feed off such soap operas, but where cycling is unique is that the great, lasting events in road cycling were founded specifically to provide copy for newspapers, by breeding this kind of intrigue.

The rivalry between Coppi and Bartali was “a great machine of financial interests”, according to Orio Vergani. Both men needed to money the rivalry could bring them. No race was worth organizing if they didn’t participate in, so they were paid to start.

Italy’s biggest sports paper La Gazzetta dello Sport also needed the pair to boost its circulation, as did the regional papers. Bianchi and Legnano needed the duo in order to sell bikes. Teammates earned far more racing for the two champions instead of racing for themselves.

There was a proliferation of opposing pairs in post-war Italy: in politics, right-wing Christian Democrats and left-wing socialists; in sports, Juventus and Inter, Maserati and Ferrari; on stage, Maria Callas and Renata Tebaldi… The Coppi-Bartali rivalry was one of them.

After Bartali’s win in the 1947 Milan-San Remo, the pair whipped Italy’s cycling fans into a state of delirium.

As Dino Buzzati wrote: “The tifosi have forgotten everything: who they are, the work waiting for them, the illnesses, luxuries, unpaid bills, headaches, love, everything except the fact that Coppi is in the lead and Bartali continues to lose ground.”

The whole of Italy split into two: the Bartaliani, and the Coppiani.

1947 Milan-San Remo

For Coppi at least, Bartali was the person who mattered in every race. He was fixated with the old man.

For example, the night before the 1947 Milan-San Remo, Coppi’s Bianchi team was sharing the same hotel in Milan with Bartali’s Legnano team. Coppi was worried about his form, so he instructed his domestiques to nobble his rival. It was well known that Bartali liked to stay up late smoking and yarning.

Coppi’s brother Serse was instructed to get Bartali out on the town and keep him up late. The race would begin early in the morning and a sleepless night could wreck Bartali’s chances. Serse took his friends Luigi Casola and Ubaldo Pugnaloni (the uncrowned Italian champion of 1943) with him.

Pugnaloni recalls: “Coppi had gone to bed early, as usual. Serse, Casola, and I took Bartali to the cinema, to see Gilda with Glenn Ford, we began smoking cigarettes, got back in the middle of the night.”

After the film, they went to eat, strolled around the station, and spun the evening out. At the back of their minds was one thought: losing sleep would cut Bartali off at the knees.

The plan failed. Coppi’s conjunctivitis got the better of him and he abandoned. Pugnaloni had insomnia after smoking too many cigarettes and quit; Casola and Serse Coppi also abandoned. Bartali was used to staying up late, and they were not.

135 wet riders departed Milan in heavy rain. The treacherous condition caked the riders and bikes with mud. Only 39 would reach the finish in San Remo. Defending champion Fausto Coppi arrive at the summit of the Passo Turchino weighed down with mud and abandoned shortly after the climb.

A group of six that escaped before the Turchino. Edmondo Toccacelli, Emilio Croci-Torti, Ezio Cecchi, Enzo Bellini, Giorgio Scrivanti and Giulio Bresci drove the pace on the dirt and snow covered roads. By the summit of the climb Cecchi was alone 9 minutes ahead of Gino Bartali, Lucien Teisseire and René Vietto.

After a relentless chase, great Italian champion Gino Bartali caught the solo Cecchi on the Capo Berta. The tireless Bartali attacked hard and dropped Cecchi 18 km from San Remo. Gino Bartali gain a brutally hard Milan-San Remo victory in 1947.

1948 World Championships debacle

The relationship reached its nadir at the 1948 World Championships in Valkenburg. The championships were contested by national teams, as today. That meant they were joint leaders of the Italian squad and expected to combine forces to represent their country.

Instead, they watched each other, neither willing to put in an effort that might have given the other an advantage.

They simply let the race go away from them, amid a cacophony of whistling from the Italian fans who had made the journey north to see one of their heroes take the gold medal. Coppi said “wherever you go, I’ll go”, and he was as good as his word, even following Bartali into the changing rooms.

The disgust of the entire country was shared by the Italian cycling federation, which banned both men for two months.

The Valkenburg debacle had far-reaching effects: Bartali would never be world champion, and the two great rivals would never truly trust each other.

Coppi’s dominant years (1949-1952) begins: 1949 Giro d’Italia

Bartali won the 1948 Tour de France, taking seven stage victories along the way. Coppi did not participate.

In 1949 Giro d’Italia, By the end of stage nine, Fausto Coppi was almost ten minutes behind leader Adolfo Leoni. In stage ten with its three major Dolomite passes, Coppi was able to come within 28 seconds of the lead.

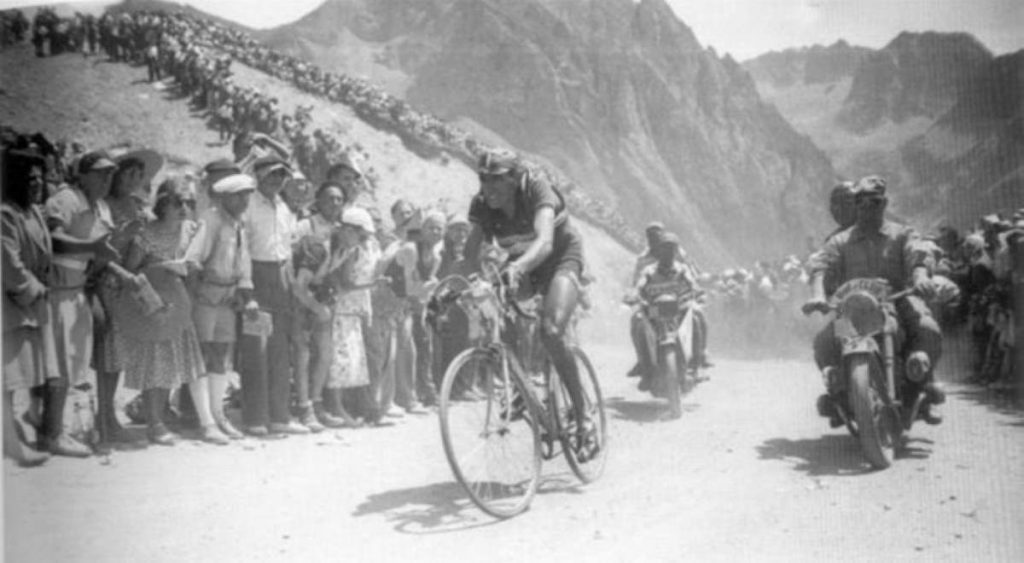

Then, in one of the most famous rides in cycling history, Fausto Coppi was first over five major Alpine passes in stage 17.

Alfredo Martini tells the story: “Coppi generally didn’t attack Bartali in the mountains, but while riding at the back of the peloton as the Maddalena climb began, he noticed that Bartali was having trouble with his brake cables near the levers and was distracted. Coppi used that moment of inattention to attack. Coppi was meticulous about his bike while Bartali was somewhat careless about his machine and as a result, suffered numerous mechanical difficulties (far more than Coppi) throughout his career.”

At this point, Coppi was still facing about 190 kilometers of racing over four more major Alpine passes. He pressed on, gaining time with every pedal stroke. Buzzati reached for a metaphor and found it in Homer’s epic final battle between Achilles (Coppi) and Hector (Bartali) in which the stronger Achilles, favored by Zeus, coldly slays Hector.

Coppi’s gap to Bartali, now chasing alone, was 6 minutes 46 seconds at the top of the Montgenèvre, 8 minutes at Sestriere, and a devastating 11 minutes 52 seconds at the finish in Pinerolo.

Martini led in Cottur, Astrua and Giulio Bresci 19 minutes 14 seconds after Coppi finished. Without Coppi, Bartali’s ride would have been considered extraordinary, and it was. But Coppi had established his supremacy in no uncertain terms.

Writers generally ascribed Bartali’s second place to age. I’m not so sure. Bartali smoked and drank, not a rare thing at that time, but he did so more than most professional racers.

Un uomo solo

Coppi, on the other hand, being a student of health and hygiene, was generally fastidious about what he ate and drank, and in that context, I wonder if Bartali had finally damaged his marvelous lungs to the point that he was vulnerable to an attack by the greatest racer of the age. Without the tobacco, what might Bartali have done?

And yet, maybe it was simply age. He confided to Buzzati that he no longer had the courage to descend at speed, though not long before (in the 1948 Tour, for example) Bartali had been a fearsome and skilled descender.

The phrase of the Rai radio commentator Mario Ferretti during the 17th stage of the 1949 Giro became legendary:

“There’s only one man in the lead: his jersey is celeste and white; his name is Fausto Coppi”.

That ride put him more than 23 minutes ahead of second-placer Gino Bartali.

Coppi went on to win the Tour de France the same year, making him the first-ever Giro/Tour double winner.

1949 Tour de France, the first ever Giro-Tour double in history

In these years, the Tour de France was run by national teams, instead of commercial teams like today. Italian national team manager Alfredo Binda didn’t want another Valkenburg debacle, so he met with Bartali and Coppi that June and laid down the law.

He told them “if the pair left the room without coming to an agreement, Italy would never forgive them and their images would be mud.” He proposed the following deal: they would each take their own gregari with them and would agree to help each other until the Tour reached the mountains, at which point they could ride their own races and it would become clear which has the stronger.

Binda made sure that he retained control of the team. He had the ultimate right to select the team. He kept the power to throw anyone off the race if they disobeyed his orders, and he established that he would be the one who told the gregari what to do.

The written agreement was signed just two weeks before the Tour at Hotel Andreola in Milan.

Coppi told his gregario Ettore Milano that if he didn’t win the tour, he would give up.

Just five days after the Tour began, he was standing by a roadside in the depths of Normandy, holding a broken bike and asking plaintively if he could go home.

On stage five, which ran over 293 km from Rouen to St Malo, Coppi broke away with the Yellow Jersey Jacques Marinelli, and 5 others. With a 6-minute lead on the field, a spectator caused Marinelli and Coppi to crash. Marinelli was unhurt, his bike was undamaged, and so off he sped. Coppi’s bike was wrecked. He was offered a bike from the Italian team car, but it wasn’t his personal spare bike and he refused to take it. He threatened to quit unless he had his own bike.

Before the Tour, Binda had asked the organizers to allow him a second team car, because he had two leaders, who might be in different places on the road. So there was a car behind Coppi, but his bike at Binda’s car, who had stopped at the feeding zone in order to ensure Bartali got his lunch. More than seven minutes passed until Binda reached Coppi. Coppi was certain that his race was over. He wanted to quit the race.

Binda initially tried compulsion: warning Coppi that if he stopped, he would be fined. That failed and the manager resorted to white lies, telling Coppi that he himself had retired from races in this kind of situation, and had always regretted it. This was fantasy, but the situation was desperate, Coppi didn’t respond.

Eventually, Binda told him that if he rode as far as the finish, he could go home the following morning, if he still wanted to. It was like talking to a wall.

Then he made Bartali wait; he knew that Coppi would be stimulated by the idea that Bartali might win if he went home. Fausto kept saying “I’m going home.” Binda said: “My fine boy, how are you going to look to your fans? You’re giving up. Goodbye glory, goodbye cash, no one will take you seriously anymore.”

Coppi was not even willing to stick with the peloton. He slowed, complaining of hunger and exhaustion. He was finally barely riding at a walking pace. Bartali, feeling he couldn’t wait anymore, took off.

Binda asked another Italian, Mario Ricci, to wait and escort him to finish. There was more psychology here. Ricci was an old friend of Coppi’s from his Legnano days and was also the best-placed Italian overall. Asking him to give up his own chances was a way of making Coppi aware that his status in the team was not being challenged. But even as he rode, Coppi continued to repeat that he was going home.

Coppi lost over 18 minutes that day, to the stage winner Ferdi Kübler, and now he was a massive 37 minutes behind Marinelli, the leader of the general classification.

Later, it turned out that Coppi felt that Binda was playing favorites by not following Coppi who had been in the lead break. He didn’t want to race on a team in which Bartali was the favorite and receiving the higher level of support.

It was a long, long night for Binda. Binda was able to convince Coppi that he had been delayed and that he wasn’t playing favorites by not following him. The story is that Coppi’s disbelief of Binda’s explanation was broken by the appearance of a blind man as the 2 were arguing. The sightless (but by no means unseeing) man walked into the hotel room with his dog. He told Coppi that he had named his dog “Fausto” and that he would never betray his dog and his dog would never betray him. With that cryptic explanation given, the blind man left. Coppi reflected for a moment and then accepted Binda’s story.

3 days later he won the seventh stage 92-kilometer time trial beating Yellow Jersey by 7½ minutes. Coppi was now sitting fourteenth in the General Classification, down 28 minutes on Marinelli. Bartali was seventh at 20 minutes.

The day before the single Pyreneen stage, 2 of Coppi’s teammates, Fiorenzo Magni and Serafino Biagioni got into a break with Raymond Impanis and Edouard Fachleitner. They beat the field by 20 minutes, earning Magni Yellow Jersey.

Stage 11, the first Pyreneen stage with 4 monster climbs, allowed Coppi to cut his deficit in half. He broke away with 1947 Tour winner Jean Robic and Lucien Lazaridès. The 2 French riders beat Coppi to the finish by a minute, after he was slowed by a flat tire.

After a day that had included the Aubisque, the Tourmalet, the Aspin, and finally, the Peyresourde Coppi now was sitting in ninth, 14 minutes, 46 seconds behind Magni who was still in Yellow.

As the Tour rode across southern France towards its appointment with the Alps, the General Classification remained stable with Magni retaining Yellow Jersey.

Stage 16, from Cannes to Briançon with the Allos, Vars, and Izoard was the first day in the Alps.

On the Izoard Coppi and Bartali broke away. The legendary duo was in a class by themselves. They were minutes ahead of the chasing Jean Robic and still further ahead of the rest of the field.

Unfortunately, Bartali flatted on the Izoard and Coppi waited. Resuming, the pair continued their destruction of the field coming in 5 minutes ahead of Robic.

The rest of the peloton didn’t start arriving for another minute and a half. This being Bartali’s birthday and Coppi feeling completely confident now of his powers, Coppi allowed Bartali to take the stage win.

Because of the time losses related to stage 5, Bartali was still ahead of Coppi in the General Classification and now donned Yellow Jersey. Coppi was now sitting in second place, 1 minute, 22 seconds behind his Tuscan teammate.

On the seventeenth stage, from Briançon to Aosta, the 2 men did it again. On the final climb of the day, the Petit St. Bernard, Coppi, and Bartali broke away. After the descent Bartali flatted. Again Coppi waited. Then Bartali fell. This time, with 40 kilometers to the finish, Binda told Coppi to go on alone. He left Bartali and rode an epic solo ride for the stage victory and Yellow Jersey.

Bartali came in 5 minutes later. Robic led the first chasers in over 10 minutes after Coppi finished. The General Classification after Stage 17:

- Fausto Coppi

- Gino Bartali @3:53

- Jacques Marinelli @12:08

- Stan Ockers @18:13

- Jean Robic @20:10

There were 2 more Alpine stages, but neither had the heavy climbing of the first 2. The top 5 in the General Classification remained unchanged.

The final challenge was the huge 137-kilometer individual time trial from Colmar to Nancy. This immense test on the Tour’s penultimate stage sealed the Tour in a commanding fashion for Coppi. He won it in a way that left no doubt that he was the deserving victor. His nearest competitor was Bartali who was 7 minutes slower. Marinelli lost over 11 minutes. Robic, a competent time trialist, lost over 13 minutes.

Coppi had done what no man had done before. In attempting the Tour for the first time in his career, he had won the Giro d’Italia and the Tour de France in the same year, and it was the first in cycling history. He was clearly the finest living rider, and, perhaps the best ever.

Final 1949 Tour de France General Classification was:

- Fausto Coppi (Italy): 149 hours 40 minutes 49 seconds

- Gino Bartali (Italy) @10:55

- Jacques Marinelli (France-Ile de France) @25:13

- Jean Robic (France) @34:28

- Marcel Dupont (Belgium) @38:59

1950 Giro d’Italia

In 1950, the handsome, popular Swiss, Hugo Koblet, had become the first foreigner -and the first protestant- to win the Giro d’Italia. When Coppi fell and broke three vertebrae, Koblet, the so-called “Pédaleur de charme”, proceeded to crush the home riders in claiming the pink jersey and, for good measure, the mountains prize. Along the way, he was helped by Coppi’s Bianchi gregari.

With the gloves well and truly off, their stricken captain detailed them to work for Koblet, and by extension to stop Bartali from profiting from his misfortune. The Italian public was initially outraged that a straniero be too strong for the best of their riders, the more so because the Giro d’Italia was to conclude in Rome, the winner to enjoy an audience with Pope Pius XII.

Italians wanted nothing more than that Gino “the pious” Bartali, touched as he was by sporting divinity, be their official sporting emissary, and Koblet subjected to a chorus of whistles during the second week of the race. Ultimately, however, so charismatic was he, and so consummate his performance, that he won them over.

He captured the hearts and minds of the sporting public and, more impressively still for a skinny cyclist, those of Italian womanhood.

1952 Tour de France, the second Giro-Tour double in history

1952 Tour de France was special: the famous Alpe d’Huez climbed first time, at stage 10, and Coppi was the first rider to win on top of Alpe d’Huez.

Coppi won 1952 Giro and Tour in the same year, repeating his 1949 success.

The most famous “bottle picture” was taken in this Tour: in which a bottle of mineral water is being passed between Copi and Bartali on the Col du Galibier. The moment itself is not important. This is a relatively common act.

Cyclists continually pass bottles to and from each other as they ride up mountains. The bottle picture does not show a moment that defines an event, for example when a race is lost and won. In the context of the relationship between Bartali and Coppi, or of the victory in the 1952 Tour de France, the moment when the old man gave his young rival his wheel on the stage to Monaco the following day was more important.

On that day Coppi could have lost the Tour, but Bartali was there and helped him out. But it is the bottle picture that has inspired the debate, the articles, the television programs.

It is not even the only bottle picture: there is another from 1952, and an earlier one from 1949.

The photo has a deeper message: by showing the two great rivals joined together by the bottle, it is also showing Italy united. That idea was important for a nation that had been just ripped apart by the war.

Bartali as Coppi’s manager

In late 1959, Coppi had signed a meager contract with San Pellegrino, a low-budget team managed by Bartali. But he couldn’t race with the team, because of his premature death.

Personal differences

They were close friends. In 1955, Coppi showed his son’s photograph first to Gino Bartali, recently retired and following the Giro as a commentator for the Italian television.

Of the two, it was Coppi who has become an inspiration to novelists, artists, and fashion designers. As a model should be, he was tall and has no jarring features that distract from his elegant clothing style (Bartali has that broken nose, other legendary Italian Fiorenzo Magni was bald with a leathery face).

But it was Bartali who was the bigger personality, who made the clearest impression on the minds of his contemporaries. Especially, his religious belief that truly set him apart. Coppi remains diffuse, hard to define; while Bartali was “il Pio Gino”.

Bartali would often take his squad to Mass before the race starts. He dedicated his wins to Ste-Thérèse of Lisieux and had her image cut into his handlebar. He raced with half a dozen medallions of Ste-Thérèse and the Virgin Mary hanging from his neck and handlebar.

There was a rumor that a little girl had seen Bartali climbing a mountain with an angel pushing him. For the Catholic church, Bartali was a gift, an ideal Catholic athlete. He produced phrases like “Faith enables me to stand the pain”, or “My jersey was often dirty, but my thoughts remained pure”.

Coppi was depicted as an atheist, to his utter disgust: he met Pius XII on at least two occasions, in 1947 and 1949. The first visit was at the instigation of Bartali, and the rumor went that he had not gone willingly.

Coppi actually had the classic faith of a Catholic peasant, but unlike Bartali, he had a countryman’s unwillingness. It was Coppi who presented all his gregari and the team manager Alfredo Binda, with gold medals depicting the Madonna del Ghisallo, patron saint of cyclists, after his 1949 Tour de France win.

Bartali’s thoughts might have been clean, but he sold many races as an amateur. In 1947 Giro, when a rider called him a “lying priest”, didn’t turn the other cheek but delivered a straight left that floored the blasphemer.

Several of his contemporaries describe him as a tight-fisted, a rider who offered money for assistance in races but never paid or came up with less than he promised. Fausto, on the other hand, didn’t say much but kept his word.

Physically and mentally, Coppi was fragile while Bartali was hard as nails: “the man of iron” was never tired, he was never felt the weather. Stomach troubles beset Coppi from time to time, but the digestive system of the “old man” was a legend in itself.

His domestique Giovanni Corrieri recalled that “he could eat stones if he wanted”. He reputedly drank up to 28 espressos a day, which might explain he never needed to try amphetamine. He would break eggs on his bars, letting the white fall to the ground and eating only the yolk. He would get through five or six in a stage. In his bottle would be watered down egg custard or sugar and water.

Bartali smoked a lot, and while the gregari might enjoy a glass of wine at dinner, Bartali had a bottle. Coppi once said, “if I had drunk just part of the wine Gino has, I’d be dead”.

In terms of lifestyle, it was actually Coppi who lived like a monk, while Bartali smoked and drank with Rabelaisian gusto.

On their bikes, they relied on different attributes. As Ettore Milano told: “Coppi had class, Gino had power”.

Bartali had stamina while Coppi had speed. Bartali used his stamina and sheer physical power, particularly in bad weather, to wear the opposition down with repeated attacks.

Coppi, on the other hand, would wait until he could sense the right moment to make the single move that would get him clear of the pack. Once away, his ability to ride at high speed alone would ensure he could not be caught.

Politically, Bartali’s beliefs were much easier to identify than Coppi’s. His father had been an active socialist, he asked Gino to hide his party card when the fascists began to rise. But Pio Gino was a close friend of the Christian Democrat leader Alcide de Gasperi, whom he met in the Vatican during the war. Inevitably, he was a supporter of the Christian Democrat party.

On the other hand, Coppi was approached by Palmiro Togliatti’s communists during the 1948 election campaign. Wisely, he turned them down. It was widely held by those close to him that he voted Christian Democrat, but that didn’t stop the political labels. There were posters: “Up with Coppi the communist, down with Bartali the Christian Democrat”.

Notes

- Eberardo Pavesi (2 November 1883, Colturano – 11 November 1974, Milan) was an Italian professional road racing cyclist. The highlight of his career was at the 1912 Giro d’Italia when he rode with the victorious Atala team, the General classification being contested by teams rather than by individual riders that year. He was later a team director, having under him racers such as Gino Bartali and young Fausto Coppi.

Sources

- BikeRaceInfo.com

- CyclingRevealed.com, 1947 Milan-San Remo

- Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi; Fotheringham W.; Yellow Jersey Press; London

- Maglia Rosa: Triumph and tragedy atGiro d’Italia; Sykes H.; Rouleur ltd.; London; 2011

- Fausto Coppi on Wikipedia

- Gino Bartali on Wikipedia

- UCI Elite Men Road Race World Champions: The Complete List [1927-2025] - September 28, 2025

- What Is Zone 2 In Cycling? - September 12, 2025

- The Turkish Flag at the Tour de France: Who’s Waving It at the Finish Line? - July 30, 2025